The headlights illuminated flashes of weathered asphalt and the odd tree dotting the dark Texan grasslands.

I turned to my nephew in the back seat. “It’s already getting scary, eh?”

Harry nodded, braces shining, hands buried in his long black sweatshirt. The last time I saw the kid he’d been several inches shorter and would still hold your hand in public.

“Why’s Waze sending us into these fields?” said Jake, tapping the phone map.

My brother-in-law Jake was at the wheel because living in New York City had left me incapable of doing many normal things, like driving a car or sleeping without earplugs. Jake had promised, though, to hang back in the parking lot so I could get some bonding time with my twelve-year-old nephew. Having just returned from a year in Israel, I was determined to make up for my long absence by giving my nephew The Most Fun Night with Aunt Jess. After scouring the internet for what to do, I landed on Creepy Hollow Haunted House, “voted the scariest in Texas!” Houston… are you ready to get your SCREAM on?

We were only forty minutes out from my sister’s Houston bungalow and yet the surrounding fields were so dim and unpopulated. I supposed my husband and I hadn’t driven much farther out of Tel Aviv before we were passing the abandoned fields bordering Gaza. That road had been dotted with scarred bomb shelters, and from behind the farmland rose the white buildings of Gaza and a plume of battle smoke. When we reached the makeshift memorial forming on the site of the music festival, we found this field, which had been covered in dancers and then their corpses, now carpeted by red wildflowers. As my husband and I walked through the red, the sky shook from the cannon fire.

“It’s scary time!” said Jake.

An orange-vested dude waved us into a parking lot beside a collection of tents and shipping containers. After Jake dropped us off at a wooden ticket booth, I realized how unusual it was for my nephew and me to be alone. Normally his mom or little brother would be here.

I said, “We are going to have fun!”

“We are,” said Harry in his new voice, deepened but not all the way.

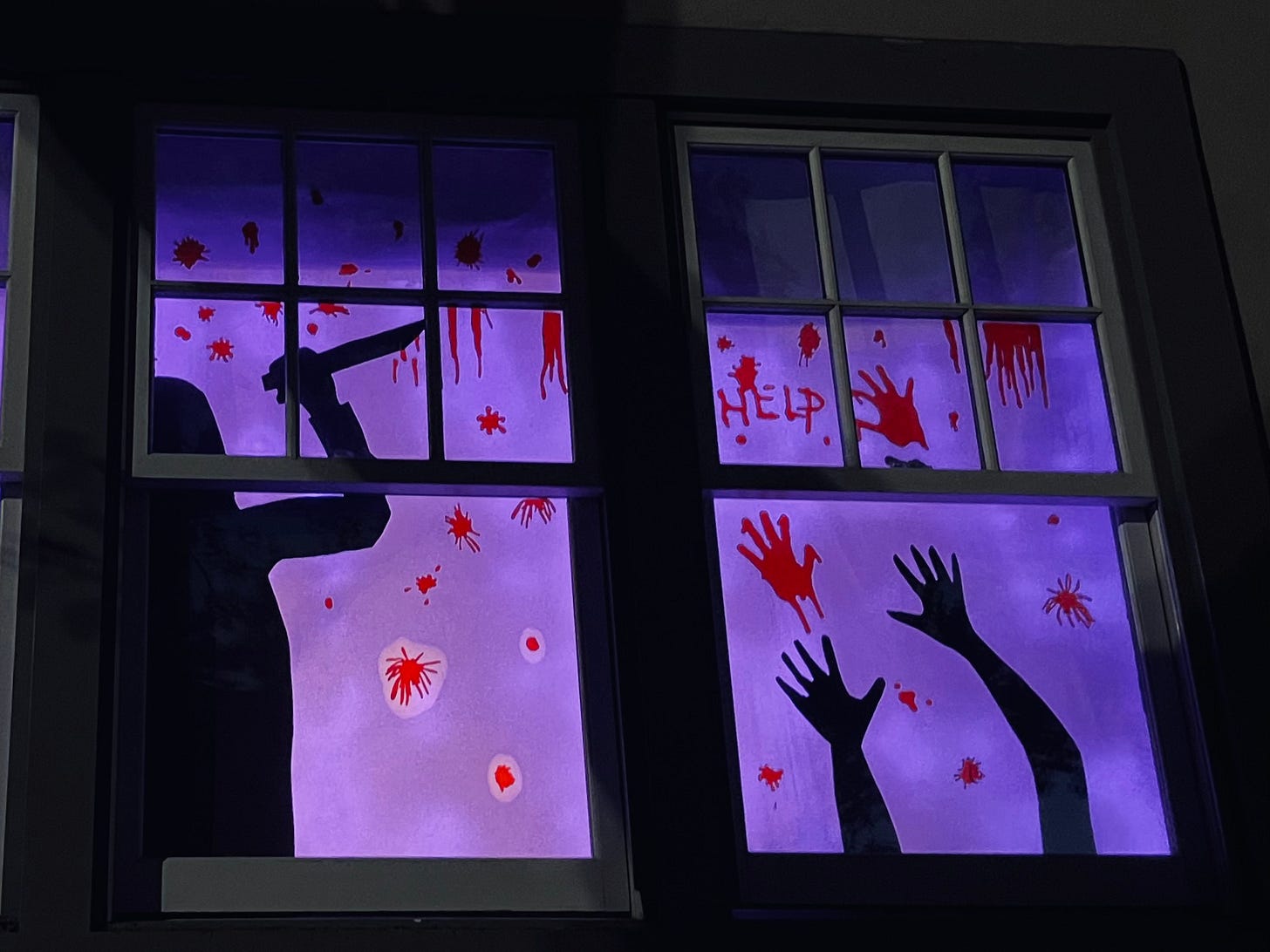

Before long Harry and I were through the gates and standing on a haunted New Orleans street, the backlot-like façades lit purplish and blue. A Day of the Dead skeleton waved from a faux balcony. It was early in the night and three weeks until Halloween. Maybe that’s why more ghouls roved the street than teen customers to scare. At fifty, I was the oldest apparition in Creepy Hollow.

“What fantastic costumes!” I exclaimed, as a wild-haired hick ran past, revving a chainsaw.

But I was already wondering what to say or do next. We’d just paid seventy bucks to enter and the only thing to do was buy voodoo souvenirs. I checked my phone, hoping to find the text that it was our turn to enter the main attractions.

“Yeah, that one is so—Haha!”

Laughing, Harry jumped to avoid being struck by a cackling Chucky-esque doll-man on a scooter.

“No!” came a young woman’s cry.

The girl lay on the ground, encircled by a motley gang of monster men. Harry and I joined the others gathering to watch her screech and laugh as a monster tugged off her shoe.

“No!” she squealed as the monsters passed her shoe back and forth.

Her shoe, I thought. Not a sawed-off breast. A shoe.

And who could picture such a thing? Gangraping a girl while tossing her breast like a hacky sack.

Trick or treat, give me something good to eat, not too big, not to small — just the size of Montreal! While my nephews were in school that day, I had worked on my novel set in Montreal, the city where I grew up. The goal had been to finish the novel during our year in Israel, but for months the manuscript sat on the computer, the date “last modified” October 6th.

That night my husband Nadav and I had been sleeping on my relative’s kibbutz near Haifa. We were a month into Nadav’s sabbatical from NYU, a month into his return to the country of his birth and first two years of life. My cousin Shira and her young family had also come from their kibbutz down south, about eight miles from Gaza. While religious Jews were celebrating Erev Simchat Torah that night, we were gathering for “The Water Holiday,” an agricultural festival held at the commune’s swimming pool.

I often think of our walk that night to the pool, how our procession grew larger and merrier as more families poured out of their modest white bungalows. When I look at the pictures from that walk, they look like “before,” even though in Gaza they must’ve already been readying the Israeli SIM cards, the AK-47s, the rocket-propelled grenades, pickup trucks, plastic handcuffs for kidnapping.

At the swimming pool, between jets of water, girls in peasant frocks circle-danced on rafts rimmed with palm leaves. Everyone sang in praise of water. While two peasant girls were lighting a floating bonfire, I turned to my husband and said, “This is so Wickerman or Midsommar. When do the murders begin?”

That night, I couldn’t sleep. The kibbutz bedroom lacked AC, and I was haunted by the kind of math that haunts a forty-nine-year-old back on an old stomping ground. During college summers and right afterward, I had lived on this kibbutz and two others, and I just couldn’t grasp how that became thirty years ago. Ten more years than the age I was during those bleary-eyed breakfasts in the communal dining hall, those nights in the “young people’s section.” Even more frightening: the next thirty years promised to go even faster. If I even got to have them. If all of them were even worth having.

I woke up on October 7th grouchy as hell and in bad need of caffeine.

“We’re no longer going on a hike today,” said Shira, handing me a glass of cowboy coffee.

“Why?”

“It’s not safe.”

Not safe? Israel has changed, I thought. In the nineties, plans weren’t scrapped because of a few missiles or a terrorist attack elsewhere. People climbed onto buses not long after a previous one had exploded.

I took my coffee to the table and joined the rest of the family in scouring our phones for news.

The English-language newspapers revealed little, and I wasn’t sure how much more was in the Hebrew ones, because my cousins and their spouses mostly shared tidbits from Twitter. Evermore difficult to believe tidbits.

I said, “You can’t trust Twitter.”

I went out into the backyard where the morning sun shone through a hedge of orange and purple flowers and sat beside Shira.

“I’m getting WhatsApps,” she said. “Terrorists have invaded Kibbutz Be’eri. They’re holding people hostage in the communal dining hall.”

“Invaded?”

She gestured for me to keep my voice down and glanced at her children, who were laughing and jumping on a trampoline.

She said, “They have lots of friends on Kibbutz Be’eri.”

Please head to the entrance of Dark Woods.

“Let’s go!” I cheered.

Harry and I ran for the attraction and joined a short line. While waiting, my nephew leaned on a wooden railing and watched an enormous, leather-clad bald man practice juggling fire.

“There’s three sections,” I said, reading from our ticket. "Dark Woods, Pitch Black, and Scare Factory.”

My nephew nodded, attention glued to the fire, its swirling flames reflected in his large brown eyes.

I really wanted us to connect. Should I ask if there’s a girl he likes? Did he like girls? Was he still fascinated by ants?

It hadn’t been my plan to go so long without seeing my family. The plan had been regular returns from Israel, especially to New York City, which had been hard for me to leave for a whole year. I remember packing my MetroCard necklace, Bagelsmith t-shirt, cap that swore “New York or Nowhere.” Through thirty years of life, the city had become woven with my sense of self, which is, I suppose, what it means to have a home. I also happened to believe, as many New Yorkers do, that my home was without doubt the place on earth. If not the best place that had ever existed.

And then I watched on October 8th — while holed up in a bomb shelter — the video of people in Times Square gleefully chanting the number of dead Jews so far: “800! 800!” I saw pictures of the seven thousand marching over the Brooklyn Bridge behind the banner “By Any Means Necessary.” Hamas called their mass murder on October 7th “Al-Aqsa Flood,” and now mobs were obeying calls to Flood Brooklyn, Flood Queens, Flood NYU. Again and again, they flooded all my familiar places with their faces hidden behind masks and keffiyehs. “Globalize the Intifada!” they shouted in Washington Square; in Union Square, a banner hailed “Long Live October 7th”; on Broadway, a Hezbollah flag fluttered over the crowd. Grand Central, the Brooklyn Museum, the subway platforms. All these places that were a part of me. And so a part of me died.

With time I’d get used to living with a deadened part, but I’ll never forget the feeling of it dying. I’ll never forget that second after I finished reading an article about a family on Kibbutz Be’eri. The terrorists had mutilated the family in front of one another —scooped out the dad’s eye, sawed off the mom’s breast, amputated the girl’s foot, chopped off the little boy’s fingers — before they finally killed them and proceeding to eat the family’s breakfast. GLORY TO OUR MARTYRS. That’s what appeared next on my screen. Those words projected by American students onto George Washington University Library. Those words glowing in an American night. And my vision blackened from the edges. I felt my head falling. I didn’t understand. I was fainting.

I cancelled my flight to JFK. At least in Tel Aviv I could leave the apartment knowing I wouldn’t have to confront neighbors ripping down hostage posters.

“Yes!” cried my nephew. “It’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre!”

We were meandering down a path through a gruesome backwoods. This was no cheap portable haunted house affair. The set-design for Dark Woods was top-notch. We passed a blood-dripping hog hanging in front of a dilapidated shack. Bloody utensils peeked out of overgrown grass. And then we entered a cemetery: a maze, really, with walls made of towering mausoleums. All haunted houses, I realized, were mazes of corridors. That’s how they moved you along, kept you disoriented and in the dark, unsure what might pop out around the corner.

Hands landed on my shoulders. Normally I would’ve enjoyed being pushed down a corridor by an unseen monster, but — even though the comparison felt totally inappropriate — I couldn’t help thinking of the hostages being pushed down real tunnels by real torturers for a year already. I was shoved around the corner, where the tunnel gained a roof and two young girls were chained to the wall. “Help me!” the girls cried as I hurried past. “Please! Help!” cried the girls who would go home tonight.

Clack clack clack. Was that supposed to be gunfire? I think they hear the gunfire through the ground. Or are some tunnels too deep? My nephew, I thought. I’m here to give my nephew The Most Fun Night with Aunt Jess. I charged ahead, putting on a good scream. My nephew giggled, and a crazed killer jumped out in front of us, his bare chest spattered with blood. Before the killer could grab me, I threw Harry at him, yelling, “Take the child! You can have the kid!”

“Noooo,” my nephew cried in delight.

The killer clutched Harry and played at trying to pull him back into the corridor. How, I wondered, did those parents survive?

“Go ahead! Take the kid!” I kept shouting, because it was cracking up the other adults and turning my nephew giddy.

“Noooo,” pleaded Harry. “Don’t take meeee!”

The line for the next attraction zigzagged inside a tent lit by black lights that turned everyone an alien green with radioactive purple-white teeth and sclera. Hoping to ensure fun by documenting it, I snapped selfies of our glowing heads and fake-gagged when I saw my nephew had flipped out his eyelids.

“Hey! I have the same one!” he said, pointing at a large teddy bear lolling in a corner.

“That big?” I chirped, though the bear was making me a little queasy.

“Uh-huh. I’ve had it forever.”

All over Tel Aviv, giant teddy bears, bloodied and blindfolded, had sat on the benches outside bars and restaurants, sometimes with their arms tied behind their backs. As the bars and restaurants slowly came back to life, these reminders of the hostages grew matted and weathered. It was surprising what could make me queasy now: teddy bears, vacuum cleaners whirring like missile sirens, the buzz of helicopters. Who knew so many helicopters flew over Brooklyn? My insides kept expecting their buzz to grow louder and louder until the chopper was flying right past the window. From our balcony in Tel Aviv, we would watch the military helicopters landing on the roof of Ichilov Hospital and the medics rushing out with gurneys to retrieve the wounded or dying soldier. It was sickening, watching this young man getting carried away, this nineteen-year-old or young father who had risked it all to protect his people, this Jew who might’ve only lived to fight Hamas because his family had narrowly survived the Nazis, and know that millions around the world were getting pleasure out of calling him the Nazi.

“YOU’VE BEEN WARNED!” barked the goth handmaiden as she opened the vault door. “Don’t take off the glasses!”

Pitch Black lived up to its name. We felt around the tunnels, jumping when a psychedelic clown sprung out. The paper prism glasses were meant to boost the neon clowns and black-lit holograms, but on top of my regular glasses for myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism, the darkness seesawed. Normally I wore contacts. If I had been at a dance festival, I would’ve been wearing contacts. So, I wondered, have some hostages been unable to see this whole time? To monitor the faces of their captors?

Jesus, I thought. Stop being so gross. Fuck you for even thinking of them while surrounded by psychedelic clowns. As if any of their hell is here with you. How dare you allow these tunnels to suggest those? How dare you? Except. Except, also how dare you not think of them? While you get to be surrounded by psychedelic clowns. If you had been sleeping on a different kibbutz that night. No. No. That’s irrelevant. What matters are the bottles of piss, the bucket of shit, revealing those six had been in that tunnel for some time before being executed. A tunnel too low to stand upright, too narrow to be side by side, too far underground for air. She was eighty pounds. Fingers slid up my neck, into my hair. I shivered exaggeratedly, spun around. My nephew’s black-lit grin was big. I loved that he felt comfortable enough to do that.

“I guess we have to eat,” I had said to my husband hours after we’d left the kibbutz.

The sun had set on October 7th. The sky outside the windows was dark, so too in our apartment, aside from the glow cast by the television news.

I opened the fridge. The shelves held only seltzer and mustard. That wasn’t unusual. New York City had the same effect on my cooking as it did the driving.

“I’ll bring back falafel,” I said, leaving the apartment.

On the street, it was dead quiet. Not a person or car was out, only the stray cats. I made my way past the Bauhaus walkups, their stucco exteriors ranging from weathered yellow to renovated white, but their windows all glowing with the same desolate light. Normally, apartments gave off different vibes, one thumping with the music of kids just getting started for the night, another exuding the silence of a souring marriage. That night, though, there was only escalating horror. I don’t remember what was learned when. Had we already seen Shani Louk’s twisted corpse being driven through a cheering crowd in Gaza? Or did that video circle the next morning? When did the number of reported hostages go from fifty to a hundred to twice as many to more? When did we hear of families being burned alive, the beheading with a garden hoe, a vagina hammered with nails?

When I reached Ibn Gabirol, a commercial strip normally bustling with outdoor cafes and evening shoppers and young people on e-scooters, it was deserted. What was I thinking, grabbing falafel? I walked quickly under the concrete arcade, past the darkened shops and bakeries. Not an hour away, the IDF hadn’t yet gained control. Terrorists were still at large. What if a car of them had made it to Tel Aviv? I was the only person out here to jump out and snatch.

I ducked into a 24/7 minimart, the only kind of establishment open, and found everyone else who had dared leave their apartment. They were lining up. Stocking up. Preparing for war. The bread and vegetable baskets were emptying fast. I called Nadav.

“Grab a tomato and cucumber,” he said. “We’ll make Israeli salad.”

While I was walking back with the small bag of groceries, sirens wailed in the dark sky. Rockets were headed for this part of the city. I started running, even though I had no idea where I was running to; I wasn’t going to make it home in the minute and a half before impact. Two teen girls, sprinting my way, waved and yelled to follow them. I scrambled after the girls into the nearest walkup, where we joined its residents rushing down the stairs to the underground shelter. In a dismal concrete chamber, we waited, glancing from the grotesque headlines on our phones to each other. The sirens gave way to thunderous booms. A man said, “So close.”

Back on the sidewalk, I picked up the pace. As I was turning onto our street, again the sirens howled. I bolted for our building, reaching it along with a fortyish man who had charged out of the dog park across the street. Only I couldn’t let the man and his German shepherd in. With the sirens wailing, I frantically searched my pockets, the grocery bag, my pockets again, but I must’ve forgotten my keys.

Just in time, the doorguy came running around the corner. He hurried us into a small closet, which probably wasn’t an actual “safe room,” but it was windowless and in the core of the building. After the explosions, I wished the man and his dog good luck getting home and headed for the elevators with my meager bag of groceries. Maybe, I thought, I should’ve bought more than one tomato, one cucumber, and some hummus.

The elevator hadn’t reached the 19th floor before the sirens howled again. When the elevator opened, I darted for the apartment. Banging on the door, I could hear Nadav shouting for our two anxious rescue dogs. He threw open the door, saying, “Ok, you’re back.” We rushed into the bedroom closet that doubled as a “safe room.” Since the nineties, all apartments built in Israel are required to have a “safe room” that can withstand rockets and chemical weapons. We shut the airtight steel door and waited between the thick walls of reinforced concrete for the explosions.

At last, three bomb shelters later, we were in the kitchen, ready to force ourselves to eat. Nadav took the grocery bag from me, pulled out the cucumber, and said, “You’re almost fifty years old, and this is a zucchini.”

“Scare Factory is the last section,” I said.

We’d reached the front of the line.

“I know,” said Harry in the deepened voice.

I hoped he was disappointed that our night was winding down. That he was having enough fun. When you rarely see your family, so much rides on one night. When everyone lives in a different part of the country, you can’t rely on decades of lazy Saturdays and sharing every holiday to bond you. You need to make one night memorable enough to stand in for half a year. At the end of your life, it means making a few weeks good enough for an eternity.

The ticket taker waved us into the factory. Harry and I wandered down a dimly lit corridor with steel-grate floors. Once again, the set design was superb. I wasn’t sure what business this factory was in, but it involved hacking up human beings, and it looked so real, the blood-stumped foot sitting atop a roller cart filled with limbs. While passing a half-mutilated corpse on a steel table, the mutilator hissed at us, brandishing a butcher knife.

Butcher knives were left behind on Kibbutz Kfar Aza. Butcher knives are not a normal weapon to bring with your incendiary grenades and anti-tank mines.

One May afternoon, I had walked around Kfar Aza with one of the only people currently living there. A sturdy, serious man nearing sixty who had come back, first to help collect the butchered bodies, then to rebuild. Squinting, he pointed to where the terrorists were first seen paragliding into the village, a patch of blue sky between us and the buildings of Gaza City. Slowly we walked past the abandoned homes, past their lonely windchimes and flower beds. Every couple of houses came one burned to a black shell, where a family may have been incinerated in their safe room. The front of every bungalow was covered in spray-painted symbols, messages left by soldiers to search and rescue teams: red Xs, yellow diamonds, black triangles. A red circle with a dot inside meant “dead civilians inside.” Many bungalows had a red circle with a dot.

We reached the “young people’s section” on the edge of the kibbutz. This section, with its two facing rows of dorm-like apartments, was painfully familiar. It looked just like the sections I had been remembering while doing mortality math on that sleepless night of October 6th. I knew so well these micro-apartments with their kitchenettes and cubbyhole bathrooms. It was in such an apartment that I lost my virginity to a young man who had recently lost his eardrums in a bus bombing. It was in such an apartment that I hung out with this pretty girl, the daughter of Moroccan Jewish immigrants, after a long walk back from a small-town roller rink. At the rink, I had felt uncomfortable when she took my hand during Total Eclipse of the Heart. In the evenings, outside these mini apartments, foreign volunteers and kibbutz kids in their early twenties would convene on filthy sofas that had outgrown inside use. While beer bottles and cigarette butts collected on a table, everyone would boast about their plans to hike to the Everest base camp or live in the East Village.

How familiar this young people’s section, except this one was pockmarked by bullets and grenades, blackened by fire, crumbling in parts. Amid the shattered glass, blown-out drywall, and sofas that had outgrown their indoor use, lay intimate items like a pair of crushed sunglasses, a lone sneaker, a bottle of Head & Shoulders.

The kibbutznik explained that the terrorists didn’t only kill people, they chopped some up.

Most of the apartments were cordoned off, but one had a sign over it: “The Family Invite You to Come into the House.” The Elkabets Family wanted the world to know what they did to their daughter and her boyfriend. Beside the door, on top of the red circle with a dot, was scrawled: “Human remains on the sofa.”

Inside, the walls and ceilings were riddled with holes. It was hard to fathom that much shooting and exploding grenades in so small a space. Sprays of bullet holes punctured the fridge. The remaining furniture was overturned, destroyed. Blood caked a collection of floor tiles. On the kitchenette counter sat a beaded bracelet, little hearts flanking the word TOGETHER. Outside the girl’s small back window lay the fields of the kibbutz, followed by the border with Gaza.

After Hamas took over Kfar Aza, regular Gazans flooded the kibbutz, pillaging televisions, necklaces, and occasionally body parts. Sometimes it was too hard, carrying everything back — they might have, say, both a mini fridge and a head — and so they dropped the head. A head was found in the fields. One young man’s head was never found. His father desperately looked for it, but he had to bury his son without his head.

The main attractions done, Harry and I stood once more in haunted New Orleans, more festive at this later hour with ghouls throwing Mardi Gras necklaces from a balcony. After my nephew caught two, I bought him a cheesecake cup. As we walked away from the food truck, I gave thought to this being Erev Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish year, when many fast and go to shul. Normally my lack of religion didn’t bother me; I drew enough connection to my people and heritage through speaking Hebrew, spending time in Israel, writing fiction that grappled with Jewish lives. But that night I wasn’t speaking Hebrew or in Israel or even in the same reality as all the people milling around me, all these lucky people who could still enjoy a faux beheading. I was alone.

Harry and I finished the night at the freak show. Sitting on the top-most bleacher, we waited for “Knives and Pointy Things” to start. A gay couple nestled beside us, the young men wrapping their arms around each other, something most New Yorkers probably don’t imagine happening in Texas. A Hispanic family spread out on the bottom bleacher. Otherwise, the stands were still empty when the first act took the stage: a comic duo who delivered their one-liners with gusto in-between jumping and headstanding on a bed of broken glass. I clapped and whooped, because I admired these actors for giving their all to a gig that surely wasn’t their dream one. And I remembered what it was like to be an artist who could still have dreams.

“Please write about this.”

We were standing in a grotesque parking lot, and the man had just learned I was a writer. On one side of us rose a wall of burned cars, rust-colored shells piled one on top of the other; in front lay rows and rows of vehicles with smashed windshields, bullet-sprayed doors, crushed fronts. This was the collection site for all the cars damaged during the massacre, while people tried to escape. It was reminiscent of the mechanical stacked parking lot I would pass in the financial district after 9/11. All those cars growing dusty, waiting for owners who had either jumped out of the towers or incinerated with them. I had been a twenty-something office temp that September morning I had cowered on the street while the debris from the second tower pelted my back. Later, in my thirties, while my husband was a post-doc at MIT, I would be walking toward the finish line of the Boston Marathon when explosions thundered over the crowd. Now my forties were ending with me staring at these cars. 1,700 of them. On their way to carry out this horror, Hamas had filmed themselves on their motorcycles, shouting: “Tens of thousands will die in the name of Islam!”

“People need to know,” the man insisted.

I was hesitating to respond, because I could promise to write about it, but I couldn’t promise to get the story out. I wrote short stories, memoir essays, the kind of stuff found in literary magazines. And I was afraid those magazines, if they didn’t steer clear of October 7th, were more likely to publish an ode to the terrorists, as N+1 did on October 10th. I was never one of those writers who felt comfortable at literary shindigs; and it had been years since I saw the world of arts and letters through idealized glasses; and yet I still wasn’t prepared for the pain of witnessing all these respected literary institutions joining the onslaught. Not all the bodies pulled out of these cars had made it to the morgue before the most esteemed literary and art reviews began publishing their countless open letters against Israel, letters signed by a who’s who of today’s most celebrated artists, letters that usually didn’t even mention the massacre or hostages. Next came the endless efforts to boycott, bully, unpublish, or shutdown any author, publisher, festival, or awards ceremony that didn’t join in the demonization. So, what could I tell this guy? That the story would need him to be the villain behind these burned cars? Sure, there were probably many in the literary world who didn’t believe this, who didn’t think he was an evil Zionist racist colonial-settling genociding apartheider who deserved this pogrom, but what did they matter? They were too afraid to print it.

I said, “I can promise to write something.”

The show paused between acts, leaving me alone for the last time with my nephew. Watching him out of the corner of my eye, I thought, Maybe that’s something you could say. To connect. Perhaps it’s what you need to say. As a Jew. You should say: Actually, Harry, Auntie Jess couldn’t quite enjoy those haunted houses. Do you know why?

Below, the youngest member of the Hispanic family, a little girl with half up pigtails, was peering about while chewing candy and happily swinging her legs. Beside us, the gay couple still snuggled. Behind the bleachers, a top-hatted ghoul kept blasting an airhorn at a table of screeching teen girls. In a corner, a group of boys were hamming it up for pictures with a giant skeleton. Everyone was having a good time here. And why should they all get to have a good time at the scariest haunted house in Texas and not my nephew?

I said, “The Scare Factory was really well-done, eh? I think that one was the best. What do you think?”

There was always tomorrow, I thought. Next week. Next year. College? Unfortunately, it seemed there would be plenty of time for Harry to feel the nightmare.

Harry nodded, his braces and Mardi Gras beads gleaming. He said, “It was all so fun!”